COVID-19 Update July 26, 2020

- icshealthsciencejournal

- Jul 26, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2020

This article contains:

Smoking Could Increase Stroke Risk in COVID-19 Patients

Six “Types” of COVID-19 Infection

Smoking Could Increase Stroke Risk in COVID-19 Patients

Written By: Nayada Deevisetpunt

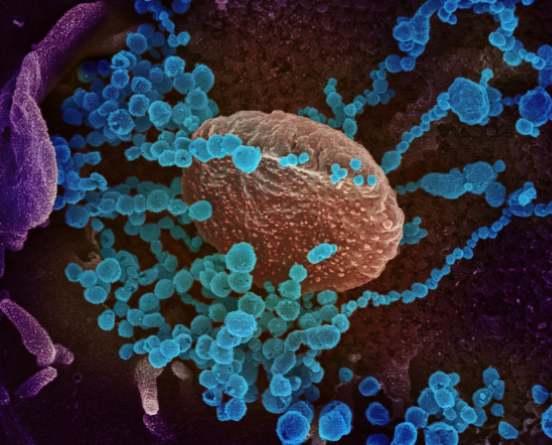

Recently, cases of delirium (an acutely disturbed state of mind), brain inflammation, nerve damage, and stroke in patients with COVID-19 have been reported from a neurological hospital in the United Kingdom. Out of all these cases, reports of stroke in COVID-19 patients are particularly prevalent and common. In fact, some reports estimate that around 30% of patients with COVID-19 experience blood clots; if these blood clots are to occur in the brain, they may be able to trigger a stroke.

Moreover, researchers from Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center found that smoking and vaping could actually increase the risk of viral infection due to damage to the blood-brain barrier (the defensive structure which protects the brain from toxins and pathogens in the blood) and an increased risk of blood clots. Smoking causes well-known damage to the lungs and the respiratory system; however, recent researches have shown that smoking could also make an individual more vulnerable to influenza.

Since smoking can affect the vascular system in the brain, researchers became curious on how this activity might affect the neurological symptoms of patients with COVID-19. The researchers first focused on the evidence concerning SARS-CoV-2 and its neurological disorders, including stroke. They discovered one study which showed that 36.4% of patients contracted with COVID-19 experienced neurological symptoms. Apart from this study, another paper also found that five cases of sudden stroke in COVID-19 patients are due to abnormal blood clotting in the patients’ large arteries. The researchers then explained that when a person smokes, his or her body is deprived of oxygen, allowing for an increase in the amount of clotting factors in the blood; as blood-clotting proteins increase, the risk of stroke increases. Luca Cucullo, Ph.D., at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, said, “COVID-19 seems to have this ability to increase the risk for blood coagulation, as does smoke. This may ultimately translate in higher risk for stroke.”

Despite lesser evidence around vaping, some studies found that vape aerosol components could harm blood vessels in the brain, affect the blood-brain barrier, and even increase the risk of stroke. Vaping could make a person more susceptible to COVID-19 by increasing the number of ACE2 receptors (receptors used by the coronavirus to infect cells) expressed in the body.

It has been concluded that smoking and vaping could increase the severity of this disease by increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors and by damaging the blood-brain barrier that could increase the risk of neurological complications. However, further research, such as comparisons of autopsy samples from COVID-19 patients who did or did not smoke, is still needed.

Six “Types” of COVID-19 Infection

Written By: Kandharika Bamrungketudom

A study of the COVID-19 infection by the King’s College London, although has yet to be peer-reviewed, has identified six classifications of the COVID-19 symptoms. Each of the six has its own corresponding symptoms and different levels of severity. With more research put in, these classifications could potentially assist doctors in treating COVID-19 patients once they could identify which categories each patient falls into.

The study carried out by King’s College London involved 1,600 COVID-19 infected participants in the UK and the US who frequently logged their symptoms onto an app between March and April. These symptoms were then analyzed to find groupings in order to answer the question of whether particular symptoms appear together or not and how this may be related to the progression of the disease.

Six groupings or ‘types’ of the disease were found in the analysis of the data. These were then tested in another group of 1,000 app users in May.

The groupings made from the study are as follows, with every patient reporting headache and loss of smell during the progression of the disease.

Flu-like With No Fever: Headache, loss of smell, muscle pains, cough, sore throat, chest pain, no fever. It is estimated that around 1.5% of the patients who are infected at the first level need breathing support.

Flu-like With Fever: Headache, loss of smell, cough, sore throat, hoarseness, fever, loss of appetite. It is estimated that around 4.4% of the patients who are infected at the second level need breathing support.

Gastrointestinal: Headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sore throat, chest pain, no cough. It is estimated that around 3.3% of the patients infected at the third level need breathing support.

Severe Level One, Fatigue: Headache, loss of smell, cough, fever, hoarseness, chest pain, fatigue. Starting at level four, the disease is referred to be “really severe,” with the estimation that around 8.6% of the patients at this stage need breathing support.

Severe Level Two, Confusion: Headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, cough, fever, hoarseness, sore throat, chest pain, fatigue, confusion, muscle pain. This stage is mostly similar to stage four, but patients experience confusion as well, distinguishing between the two stages. It is estimated that almost 10% of the patients at this stage need breathing support.

Severe Level Three, Abdominal and Respiratory: Headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, cough, fever, hoarseness, sore throat, chest pain, fatigue, confusion, muscle pain, shortness of breath, diarrhea, abdominal pain. it is estimated that almost 20% of the patients at this stage need breathing support. It should also be noted that only 16% of the stage one COVID-19 patients require hospitalization, compared to patients in stage six, where nearly half of the patients require hospital care.

Another trend that was also noted is that the patients that are more severely infected (diagnosed to be in stage 4-6) with COVID-19 tend to be older, frailer, overweight, or have pre-existing conditions such as diabetes or lung diseases.

From this study, researchers were able to develop a model by gathering information of the patients’ age, sex, BMI, pre-existing conditions, and symptoms just around five days after the onset of the disease. The model predicts which stage of the disease the patient would fall in more accurately than if only age, sex, BMI, and pre-existing conditions are to be taken into account without the symptoms. This could then be used to predict the level of hospital care the patients may need to receive, monitor those who may need the most help, and offer early interventions against the disease.

Comments